Tinker v. Des Moines is a landmark Supreme Court case that significantly expanded the First Amendment rights of students in public schools. The ultimate decision within this case, is still widely debated as the limitations and censorship of student journalism remain.

Introducing, Tinker v. Des Moines, 1969, and Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier, 1988. These are two of the most important cases that ultimately defined students’ rights to speech and protest in schools. Although, just because they held strong cases regarding the First Amendment, their verdicts set very different precedents for student expression.

In December of 1965, John Tinker, Mary Beth Tinker, and Christopher Eckhardt wore black armbands to their schools in Des Moines, Iowa, as a silent protest against the Vietnam War. The school district banned armbands as a result; leading to the suspension of both students after their refusal to compromise. Their families took legal action, arguing that the school violated their First Amendment Rights.

The case hit a groundbreaking 7-2 decision, when the Supreme Court sided with the students. The ruling stated that students do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.” As long as student speech does not cause a “material and substantial disruption” to the school environment, it is protected. This shaped freedom of speech in schools today as it affirmed that schools cannot censor student expression simply because they disagree with its message.

However, nearly two decades later the Supreme Court would take a different stance when it came to student journalism. In Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier (1988), the principal of Hazelwood East High School removed two pages from the student newspaper that contained articles on teen pregnancy and divorce. The student journalists argued this was censorship and a violation of their First Amendment Rights.

This… did not go their way however. In a 5-3 decision, the Court ruled against the students, stating that school-sponsored publications are different from personal student expression. Because the newspaper was part of the school’s curriculum, administrators had the right to exercise editorial control as long as their actions were “reasonably related to legitimate pedagogical concerns.” In other words, if a school-sponsored activity does not align with the school’s educational mission, administrators have the authority to regulate its content.

The key difference between these two cases comes down to a technicality. Tinker protects independent student expression without any setbacks, while Hazelwood allows schools to regulate speech when it is a part of their curriculum. The ruling established the constitutional rights of students to express themselves in controversial topics, with the exception that it does not disrupt the educational environment.

Tinker set a high bar for limiting student speech, requiring proof of substantial disruption. Hazelwood, on the other hand, gave schools more discretion over what students could publish in school-funded media.

But how do these landmark cases affect students today, especially here at John Dewey High School?

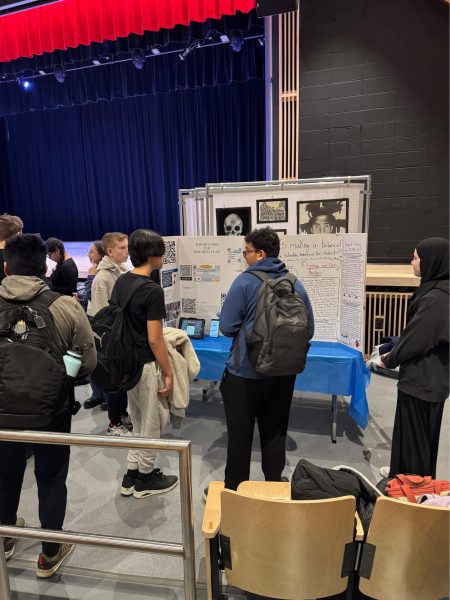

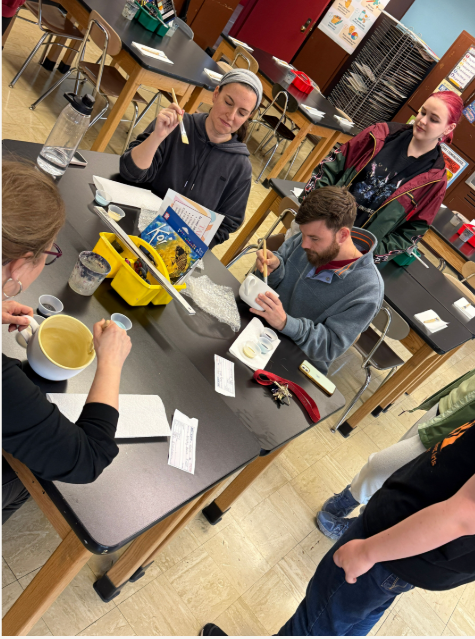

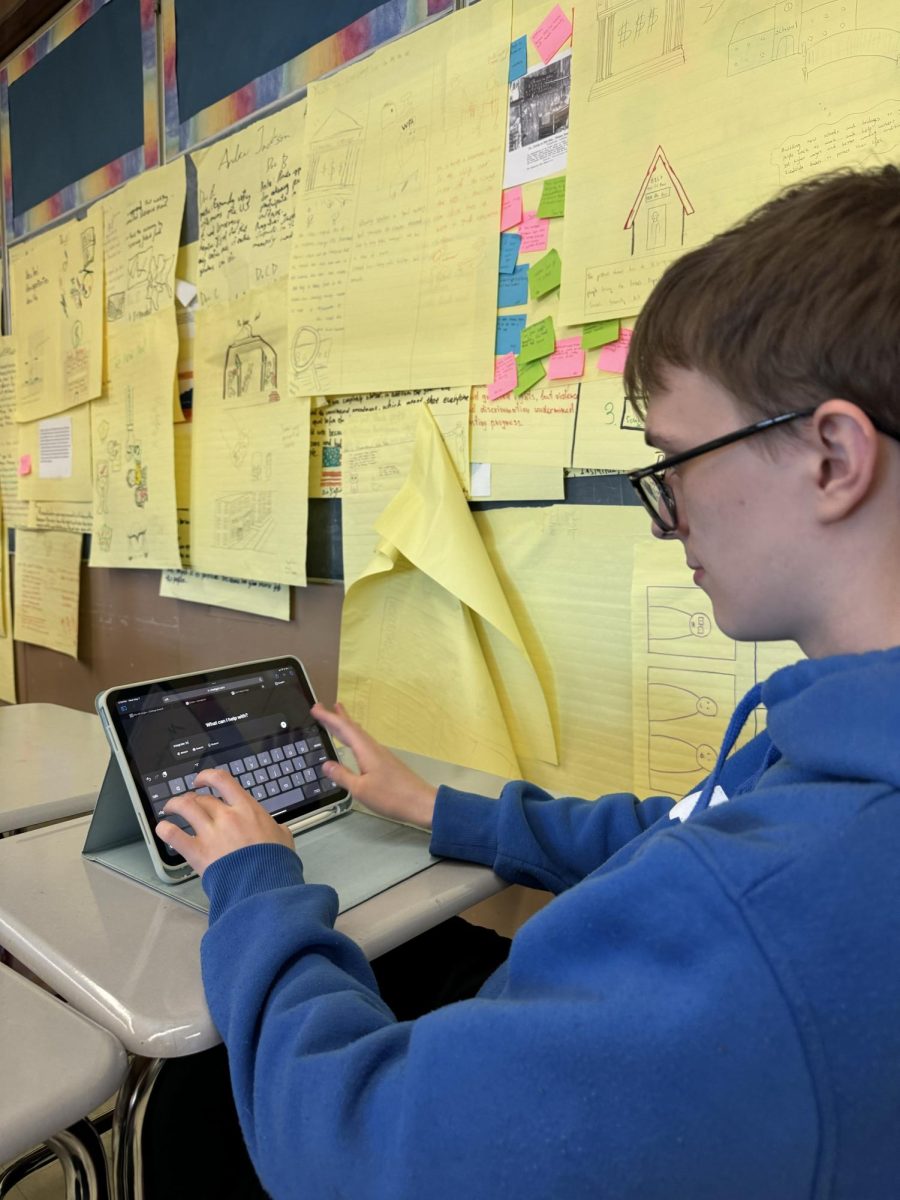

With the rise of digital media and student journalism, the balance between free expression and school oversight continues to evolve. John Dewey’s own journalism team, for example, experiences both the freedoms Tinker guarantees and the limitations Hazelwood permits. The school’s administration supports student-led reporting but maintains editorial oversight over articles published under school funding.

Karen Lin, a junior and student journalist, shared her thoughts about the history of Journalism and how these two major supreme court cases shaped it, “I wouldn’t say that Dewey has ‘coverage restrictions’ specifically, but I do acknowledge that a lot of students hesitate when trying to cover more controversial topics.”

Mindy Zou, a senior at John Dewey High School, and the member of the JDHS Dragon Scale’s Mock Trial Team added, “Well as a partial reader of the Dragons Den publication, it seems to be a fine line between student controversy and keeping the school’s reputation. I feel like we understand that we have certain rights when it comes to Student Journalism but in the end, the school has the final say when it comes to certain content.”

Lin later states, “If the school ultimately decides whether or not to “allow” our publications, then it’s hard to defend “free speech”.”

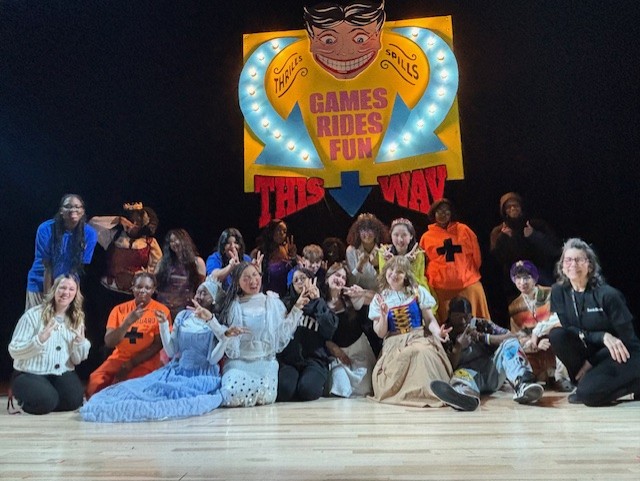

As new challenges emerge, from social media disputes to school policies on digital expression, the legacy of Tinker and Hazelwood continues to shape student press freedoms at John Dewey High School and beyond. The debate regarding the extent of student voice is moderated, proceeds today.

Alan Lener, a committed John Dewey High School Social Studies teacher since 1996, included that he saw “potential” in all his students in terms of opinion and advocacy.

The contributions, and existence, of this very news press would not be possible without Tinker v. Des Moines. These cases are a reminder that advocacy ultimately results in change, and an example of the free speech that journalists and students in John Dewey High School should strive toward.